Homelessness Begins at Home

Noterdaeme and Isengart trace the origins of the Homeless Museum from its humble beginnings to its newest incarnation as a home-museum.

Recorded in Brooklyn, July 2005

Daniel Isengart: First, let's talk about the name of your art project. On the one hand, one might expect that the Homeless Museum is a museum that represents the subculture of the homeless, much like New York's Lower East Side Tenement Museum, which focuses on America's urban immigrant history. On the other hand, the name could imply that the museum itself doesn't have a home. Which one is it? Or is it something else altogether?

Filip Noterdaeme: Of course, HoMu is far from being anything like an anthropological institution. HoMu's language is the language of art, not science or research. For one, I should point out that I am using the term "homeless" quite loosely, sometimes synonymous with "powerless" or "clueless," "unwanted" or "neglected" and feel free to apply it to people across social and economical borders. In terms of the Museum itself being homeless, HoMu will by definition always be homeless as an art collection that doesn't fit in the climate of today's art world. At this point, it is merely squatting in my rental two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn. Still, HoMu also exists online, as a virtual museum, as well as a conceptual idea that can take on many different guises, such as the catalyst behind a protest action at MoMA, held in 2004. At a recent panel discussion at the Guggenheim Museum, the art historian Boris Groys argued that "art has no definite place today" and that it is "a documentation of something that is fundamentally absent."

DI: Where do you stand in terms of homelessness as a fate so many people in this city endure?

FN: It's a terrible thing that has affected me deeply. I look at them with horror, realizing that, because of my unwillingness to conform and my chronic inability to carve out a life of financial stability for myself, this could be me someday. I think that homelessness is one of the last taboos of our society, and obviously one of the only subjects that hasn't been appropriated by commerce, which by itself makes it an intriguing subject for art. HoMu, without being literal, is offering a striking view on the conditions of homelessness. The homeless personify our internal fear of failure. They live out the American nightmare as opposed to the American dream. We look away and remain in denial that we live in a pitiless society that doesn't properly prepare everyone for the pressure of success that has become the predominant feature of our daily lives. My inspiration for the Homeless Museum came from seeing these poor people whose situation seems beyond repair. I always say that homelessness begins at home. What we see on the streets is the last phase. I am not a social worker and I don't say that I have a solution to end homelessness, but I instinctively feel that homelessness is a slow process that begins with the deconstruction of the ego. Both as an artist and as an art educator, I am always trying to wake up people's senses and engage them mentally, because I believe that this is the only way to remain truly alive and live well. If I had to sum up HoMu's purpose in one phrase, that would be it.

DI: You have worked for many years at the Metropolitan and the Guggenheim Museum. How has working for these institutions influenced you?

FN: For one, it's a world I feel very much at home in. Being close to their great art collections has been tremendously gratifying. But I have also been able to look behind the curtain and have grown increasingly frustrated with the rising level of opportunism and commercialism within the cultural sector. It has made me doubt the sincerity of many professed art lovers.

DI: Was this insight your inspiration to create your own counter-museum?

FN: Very much so. HoMu offers a cultural antidote to museums that have, by and large, turned themselves into businesses, a phenomenon Frank Lloyd Wright foresaw in 1958 when he stated that the very heart of the Guggenheim Museum would "go out when the museum as business comes in." HoMu really started out as a mockery of the cultural institution-as-enterprise. I would pose as the director of the Homeless Museum and for example write official-sounding letters to an established museum, referring to its publicized financial troubles and proposing a lucrative collaboration by squatting on its rooftop. The HoMu archive encompasses by now dozens of such letters sent to institutions and commercial conglomerates. In this realm, I was very much influenced by the work of a compatriot artist, the late Marcel Broodthaers, who created his own fictive museum, the Musée d'Art Moderne in 1968.

DI: But eventually you took the next step?

FN: As time went by, HoMu became more real and took a life of its own. I began to create real art pieces in addition to the conceptual writings, and it became more and more important for me to draw a distinction between Noterdaeme the artist behind HoMu and Noterdaeme the museum director. As a matter of fact, the first pieces I did were ready-mades in the Dada tradition, as I wanted to remain as far removed from the act of creation as possible. The $0 Collection, for example, is a color-coordinated assembly of found objects, very much like those you find lined up on the streets of New York, sold by homeless scavengers. Accordingly, all of HoMu's art works are called "acquisitions" and are not presented as works by Filip Noterdaeme the artist. In the course of two years, the museum "acquired" several installations, paintings, and sculptures. I needed to find a space to exhibit them. In one of HoMu's first videos, you see a staged meeting of the museum's board of trustees, all fictional characters, who discuss whether the Homeless Museum should acquire a home. In the video, no decision is being made. Two years later, it happened, and it happened in my home.

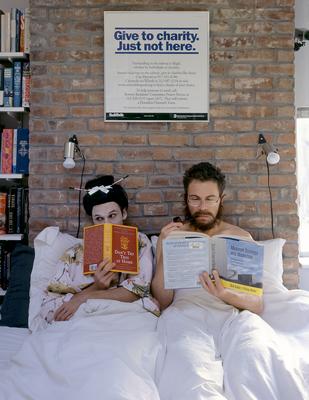

DI: What is it like to live in a museum?

FN: It's wonderful. On one hand, it is completely mad, but then again, to me it's the most normal of things. As the child of a diplomat, I grew up in a world where the private and the public were constantly blurred: the embassies we lived in where both residential and representative, designed to accommodate large receptions and official dinners on a weekly basis. At HoMu, visitors are torn between a sense of entering somebody's intimate fantasy world and an earnest will to grasp the underlying meaning of the project as a whole.

DI: Tell our readers how HoMu operates.

FN: We are running the museum without any funds other than our own income, and we remain free of charge for all visitors. The only moment money comes in is when people sign up as members, but we ask members to give their contribution to a homeless individual of their choice instead of giving it to us. Some people come to the museum expecting it to be some kind of charitable organization, but we are turning it around, asking them to get their own hands dirty and do it themselves. All in all, I am having a blast, and usually, once visitors realize that this is an unpretentiously eccentric environment, they begin enjoying it, too. Most installations, like the Homeless Simulator, are interactive. We're offering a guided audio tour and there is a café that serves food inspired by Broodthaers' works, as well as a shop display. Visitors also get a chance to enter the museum's "inner sanctum," the bedroom, and chat with the director.

DI: So what is the next step for HoMu?

FN: Some people have recommended I turn it into a non-for-profit organization, but I have decided against it. I do not intend to become part of the very machinery that I am criticizing for being self-serving. I abhor bureaucracy and insist on remaining independent. Having said that, I am planning to create a new HoMu outpost, the New Homeless Museum, with the help of an art foundation, and will probably soon hold a de-accession sale to raise funds for the first time.

DI: What would you like to be best known for?

FN: For shaking up the art world by making fun of it while touching on serious subjects. As art critic Dave Hickey wrote, "We live in a culture in which solemnity, earnestness and sincerity are equated with seriousness. Unless you wrench art away from public virtue, we have absolutely no way to make it live." Everything I do is an anarchic blend of absurdity and sincerity. Even this interview is fiction.

DI: But who wrote it?

FN: You did!